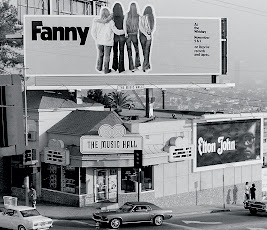

This hugely enjoyable documentary—which screens as part of this year's BFI Flare on March 18 and 19—charts the rise, demise and resurrection of Filipina-American rock band Fanny. It is probably quite accurate to take the view that Fanny were, and are, something of a band's band, and this conclusion is borne out by the parade of talking heads that populate Bobbi Jo Hart's absorbing film; among those interviewed here are producer Todd Rundgren, Kate Pierson of the B-52s, Bonnie Raitt, Def Leppard's Joe Elliott, Earl Slick, and Gail Ann Dorsey. Of course, the band themselves do much in the way of talking here, although original member Nickey Barclay is conspicuous by her absence; word has it that Barclay is quite happy for her time with the band to stay firmly in the past. Although Fanny are a very different act from Canadian heavy metallers Anvil, whose career was given a tremendous boost by the release of Sacha Gervasi's excellent Anvil! The Story of Anvil, it is easy to imagine Hart's film similarly renewing interest in its subject.

Fanny were formed in California in 1969, with the initial lineup consisting of Barclay, Alice de Buhr, Brie Brandt, and sisters June and Jean Millington. Shortly before the recording of Fanny's debut album—they were the first all-female rock band to release an LP through a major record label—producer Richard Perry, firmly of the opinion that the group would fare better as a four piece, dismissed lead vocalist Brandt (who would return a few years later to take de Buhr's place on drums). Five years and as many albums on, Fanny called it a day, and the final incarnation of the band featured Suzi Quatro's sister Patti, who had replaced June Millington. Ironically, Fanny's biggest hit arrived in the wake of their split, with "Butter Boy"—penned by Jean Millington about her ex-boyfriend David Bowie—climbing into the Billboard top 30. Although Fanny were the envy of many musicians—after all, they had a multi-album record deal and got to tour the world—it's clear that they never made the impact they, and many others, felt they deserved.

The band actually enjoyed more success in the UK than in their native US, with the glam rock stomp of their later recordings proving popular with British audiences of the time, and Fanny recorded their third album in London's Apple Studios, with longtime Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick lending his hand to the production; fittingly, a Beatles cover ("Hey Bulldog") was included on the record. If these recording sessions formed a link between the group and the UK's greatest-ever band, Fanny had an even stronger connection to Britain's greatest-ever male solo artist: for decades after his relationship with Jean had ended, David Bowie championed Fanny's music, and it's obvious that he genuinely considered them to be criminally underrated. Jean would go on to marry and have children with Bowie's guitarist Earl Slick, who is good value in Hart's film, as is the Thin White Duke's bass player Gail Ann Dorsey.

On the evidence presented in Fanny: The Right to Rock, it is not difficult to understand what Bowie saw in this band; Fanny were incredible musicians and songwriters, and it is highly unfortunate that they first appeared during a period when it was hard for an all-female rock band to be taken seriously. While Fanny may have been ahead of their time, they paved the way for other bands such as the Runaways and the Go-Go's, whose respective frontwomen Cherie Currie and Kathy Valentine are featured here; they and all the other interviewees offer useful insights, yet the film's standout presence comes in the form of the witty, engaging and charismatic Brandt. Happily, Fanny: The Right to Rock proves that the band weren't content for their story to end in the mid-70s, and Hart follows the efforts leading up to the formation of Fanny Walked the Earth, a new iteration of the band which saw Jean, June and Brie record together for the first time in nearly half a century; the resulting self-titled album—like the film that documents its making—is a very strong work, one that should see Fanny receive the recognition that unjustly eluded them first time around.

Darren Arnold

Images: BFI