Wednesday, 13 August 2025

Almayer's Folly (Chantal Akerman, 2011)

Friday, 1 August 2025

The Captive (Chantal Akerman, 2000)

First released in 2000, Chantal Akerman's The Captive is an updating of Marcel Proust's The Prisoner, the fifth volume of his epic novel In Search of Lost Time. This striking, formally rigorous film reframes Proust's study of obsessive control to great effect; perhaps surprisingly, Akerman made just one other literary adaptation, her eponymous 2010 film of Joseph Conrad's debut novel Almayer's Folly. The Captive is one of four of the late Belgian director's features—the others being Golden Eighties, Tomorrow We Move and De Afspraken van Anna—that have recently been restored in 4K by the Royal Film Archive of Belgium.

The Captive follows Simon (Stanislas Merhar), a rich idler who becomes increasingly obsessed with his girlfriend Ariane (Sylvie Testud). Simon dictates and monitors every aspect of Ariane's life, and is particularly interested in her friend Andrée (Olivia Bonamy), with whom he suspects she is having an affair; Ariane, for her part, is compliant yet inscrutable. The long takes and attenuated pacing allow the audience to fully immerse themselves in the characters' fractured psychology, while the immaculate cinematography, by the Léopoldville-born Sabine Lancelin, lends an icy claustrophobia to the proceedings.

Merhar, who later played the title role in the beguiling Almayer's Folly, delivers a fine performance as Simon, deftly capturing the character's vanity and neuroses as he attempts to tighten his grip on Ariane. Testud, who would also go on to reteam with Akerman (on Tomorrow We Move), is equally impressive, with her Ariane embodying an opaqueness that keeps her a mystery to Simon and the audience alike. As the film presents the fraught dynamic between the ethereal Ariane and the controlling Simon, Akerman explores wildly contrasting ideas of love and the blurred lines that sit between devotion and possession.

It may well be that Ariane is as unknowable to Simon as Proust is to the non-francophone; it's been posited that English translations of In Search of Lost Time—of which there have been several—largely fail to illuminate the text. There is also the challenge of another kind of translation: that of adapting Proust, who was openly dismissive of cinema, for the screen. Prior to The Captive, filmmakers Volker Schlöndorff (Swann in Love) and Raúl Ruiz (Time Regained) grappled gamely with other volumes from the same novel, but it is perhaps Chantal Akerman's haunting effort that best captures the essence of Proust's magnum opus.

Monday, 14 April 2025

Hot Milk (Rebecca Lenkiewicz, 2025)

Hot Milk, the directorial debut of Ida screenwriter Rebecca Lenkiewicz, is a beguiling adaptation of Deborah Levy's eponymous Booker-shortlisted novel. Lenkiewicz's film, which premiered at the Berlinale and was selected for last month's BFI Flare, examines the knotty relationship between Sofia (Emma Mackey) and her controlling single mother Rose (Fiona Shaw), who are staying in an apartment in the Spanish coastal city of Almeria. But despite the sun-dappled locale, this is no holiday: Rose is receiving treatment from a local doctor, Gómez (Vincent Perez), for an undiagnosed condition that confines her to a wheelchair.

As Sofia seeks some respite from her rather suffocating domestic situation, she encounters—and becomes enamoured with—flighty bohemian Ingrid (Vicky Krieps), yet this dalliance eventually proves as frustrating as the fraught relationship with her mother. Sofia decides to mix things up by heading to Greece (which is in fact where the entire film was shot) to visit her father (Vangelis Mourikis), who now has a new family and is unable to provide much in the way of the fulfilment she so obviously craves. In a development that underlines Rose's extremely manipulative nature, Sofia is abruptly recalled from her Greek sojourn.

Clearly, Rose is a very damaged individual, and it's implied that her symptoms are largely psychosomatic. Yet Shaw's immense, nuanced performance leads us to both pity and scorn this troubled soul, who dismisses the incremental academic progress made by Sofia while simultaneously cherishing it as a means to infantilise her daughter, therefore preventing her from growing up and flying the nest. For her part, Sofia—whose doctorate is currently on hold, at least partly because of Rose's treatment—alternates between dutifully caring for her mother and barely tolerating her endless, grating requests for suitable drinking water.

Mackey, hitherto best known for the Netflix series Sex Education, responds to the marker laid down by Shaw and delivers a turn to match that of her seasoned co-star, while Luxembourgish actress Krieps is good value in a rare supporting role. Given that Levy's book is one in which much hinges on Sofia's interior life, translating it to the screen is no easy task. When reviewing a title from last year's Flare—Orlando, My Political Biography—I wrote about the challenges of adapting such novels; as with that film, the haptic, hypnotic Hot Milk takes a sideways approach to adaptation, and the results are highly impressive.

Tuesday, 2 July 2024

Orlando, My Political Biography (Paul B. Preciado, 2023)

Friday, 5 January 2024

USAH (Giorgio Clementelli, 2023)

Monday, 30 October 2023

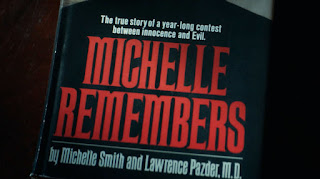

Raindance 2023: Satan Wants You

Saturday, 18 March 2023

watchAUT: Frau im Mond / Rubikon / Matter Out of Place

Saturday, 19 March 2022

I Want to Talk About Duras (Claire Simon, 2021)

Tuesday, 11 January 2022

Looking for Muriel

I'm very grateful to each and every person who buys my books, so should you choose to order Looking for Muriel: A Journey Through and Around the Alain Resnais Film, please know that your purchase is greatly appreciated. The book is available directly from the publisher, as well as from a number of retailers, including Walmart, Amazon and Google, the last two of which are linked to at the very bottom of the page (to find these buttons, be sure to use the desktop version of the site and scroll all the way down). If you'd like to check if the book is available from your country's Amazon, simply visit that particular store and plug the following number into the search box:

Friday, 15 October 2021

Prayers for the Stolen (Tatiana Huezo, 2021)

Wednesday, 18 August 2021

Benedetta (Paul Verhoeven, 2021)

Monday, 19 July 2021

Mothers' Instinct (Olivier Masset-Depasse, 2018)

Mothers' Instinct gives Belgian actress Veerle Baetens a great opportunity to flex her acting muscles; the Brasschaat native has previously impressed with strong turns in the likes of Robin Pront's The Ardennes and Felix van Groeningen's The Broken Circle Breakdown, with her performance in the latter receiving wide acclaim while netting several Best Actress awards from film festivals around the world. These three films provide evidence of Baetens' considerable range as a performer, and the most recent of these titles, the 1960s-set Mothers' Instinct, is a sly, clever work, one in which the actress appears to be having a great deal of fun as she plays a character who keeps us guessing all along; there's a great game going on between Baetens and her co-star Anne Coesens, as both play equally inscrutable characters in this mischievous, simmering thriller.

Baetens' Alice and Coesens' Celine live next door to one another and are on very good terms, yet even this close friendship is eclipsed by that of their two little boys, who spend a great deal of time together; the film isn't that old before Celine's son falls to his death from an upstairs window, and it is from this tragedy that the film's setup clicks into place: Alice feels that Celine is tacitly blaming her for what happened. While Alice was the sole witness to the accident but didn't have enough time to alter the terrible course of events, she was in no way responsible for the child's death; but whether it's a form of survivor's guilt or something else, Alice is uneasy around Celine, and even suspects that the bereaved mother is consumed by a jealousy that will drive her to take revenge on those on the other side of the wall. But is any of this real, or simply a state of mind on the part of Alice? Celine certainly seems very fond of Alice's son, but the boy's jittery mother just can't take this kindness at face value.

Based on a novel by Belgian author Barbara Abel, Mothers' Instinct is a taut, imaginative work, one which comes to the boil nicely as all the passive-aggressiveness eventually gives way to something more overtly hostile. While many have likened the film to the work of Alfred Hitchcock, it actually feels more closely related to Claude Chabrol's thrillers of the 60s—although, given that Chabrol was known as the "French Hitchcock", perhaps it doesn't really matter which, if either, of these masters you choose to reference. The decision to set the film in the 1960s means that we're treated to an immaculate recreation of the decade's styles and fashions, all wrapped up in a sumptuous colour palette; you strongly suspect that Mothers' Instinct wouldn't be quite as much fun without these sets and costumes, given that the production design is as big a star as either of the excellent leading ladies.

While Veerle Baetens' performance may be the more eye-catching, Anne Coesens matches her co-star every step of the way, and there's a lot of nuance in her portrayal of the grief-stricken Celine. The classy all-Belgian affair that is Mothers' Instinct seems a rather unlikely work from Olivier Masset-Depasse, a filmmaker previously best known for 2010's Dardennes-esque Illegal, but it's always nice to see a bit of versatility behind the camera as well as from stars like Coesens and Baetens; Masset-Depasse is actually married to the former, who has been an ever-present in her husband's theatrical features, which date back to 2006's Cages. While he hasn't made too many films, Mother's Instinct proves that Masset-Depasse continues to grow as a filmmaker, and it will be worth keeping an eye on his next career move.

Wednesday, 5 May 2021

Maya the Bee 3: The Golden Orb (Noel Cleary, 2021)

Following on from both her eponymous 2014 big screen adventure and 2018's The Honey Games, lovable bee Maya makes a welcome return to cinemas with The Golden Orb. Maya's third feature film was due to be released last year but was put back on account of the COVID-19 pandemic; rather than go direct to streaming—a route that has become commonplace over the past year or so—The Golden Orb has been held over until cinemas are able to reopen. Although it's a second sequel, The Golden Orb works just fine as a standalone film, so no prior knowledge of Waldemar Bonsels' apian creation is necessary; it's hard to believe that it's now well over a century since the publication of the book featuring Maya's first adventure. With its simple message, vibrant colour scheme and appealing, top-drawer animation, The Golden Orb, like its two predecessors, is aimed squarely at younger children, but there is much here for older children and adults to enjoy, too.

When Maya and her friends finally reappear in cinemas (on May 17), you will soon discover that the title character and her best friend Willi don't share the patience of the film's distributors, as their eagerness to say goodbye to lockdown sees them emerge prematurely from their hive; one calamitous glowworm-related incident later, and the bees' queen decides to separate the pair before they can cause any more trouble. In all fairness to Willi, it was Maya who was the architect of the situation, but irrespective of how the blame should be apportioned, the queen feels it will take something remarkable to make her change her mind regarding the sanctions she plans to impose on the young bees. Thankfully, something remarkable does come the way of Maya and Willi when they are entrusted with the orb of the title. Spoiler alert—the orb is actually an egg, from which an ant princess duly hatches.

While this development occurs quite early on in the film, there's still plenty of well-paced excitement to come as the two bees strive to deliver the princess to the other ants; it's quite a mission, and there's an added complication as some dastardly beetles—who are engaged in a turf war with the ants—are going to extreme lengths to get their claws on the cute newborn, who has formed quite an attachment to a surprised Willi. Along the way, the bees encounter a couple of well-meaning but rather clueless soldier ants who, as so often seems to be the case with ants in animated works, are sporting army helmets. The energetic proceedings are occasionally punctuated with songs, with nefarious beetle Bumbulus proving to be the real star of the show when it comes to taking the mic. As the pursuit rages on, the princess' party offer an olive branch (or rather, a leaf) to the beetles, which hints that unity may be a better option for all concerned.

Given the uncertain futures of cinemas and the films which play in them, The Golden Orb's release provides an excellent opportunity for families to get along and support both the film and the venues that will be hosting it; filmgoing is a part of life that can be hard to return to once you've been away from it for a while, but a trip to your local cinema is fairly certain to provide a quick reminder of the joys of watching a film on the silver screen. Three years ago, I saw The Honey Games in a cinema in France; back then, none of us had any idea of the drastically changed world its sequel would be released into. While there is little doubt that the viewing habits of many will have changed permanently during lockdown, the efforts of those behind the The Golden Orb's release deserve to be rewarded with solid footfall as the film rolls out in cinemas; this cheerful, optimistic slice of animation is just the thing to jump-start your year at the movies. Showtimes and tickets are available here.

Darren Arnold

Images: Strike Media

Sunday, 21 March 2021

Tove (Zaida Bergroth, 2020)

Although not exactly a writer who shunned all publicity à la J. D. Salinger, it is fair to say that the Moomins were always the public face of Jansson, but as Tove—which screens at BFI Flare until March 28—proves, she led an interesting, full life, one that was by no means lacking in drama. The film begins as WW2 is drawing to a close; once the conflict ends, Tove, now in her early thirties, is swept up in the new sense of optimism and freedom that is swirling through society, and she sets up in her own place where she spends her days honing her skills as a painter. Tove's stern sculptor father is critical of his daughter, not so much because of the paintings she produces, but rather because of her unconventional approach to both life and work; her mother, on the other hand, is far more sympathetic. Tove mixes with a bohemian circle, and open relationships are quite common among those she socialises with; it's not long before she enters into such an arrangement with Atos, a prominent member of parliament. While both Tove and Atos seem quite content with this setup, a complication soon arrives in the form of the aristocratic Vivica, a theatre director who quickly captures Tove's heart.

Tove is a stylish and engaging work, one which features a superb turn from Alma Pöysti as the title character. Pösyti, in her first starring role, delivers a well-judged performance as she deftly wraps the clearly sensitive (and occasionally troubled) Jansson in a puckish exterior. It is hard not to feel the jolt of pain Tove experiences as she unexpectedly catches a glimpse of Vivica across a crowded Parisian café, especially when we can clearly see that she has far better options than chasing after the fickle theatre director. Yet it is from her personal relationships—with friends, family, lovers—that we discover the inspiration for the various Moomin characters; like so many authors, Jansson used real-life encounters as part of the basis for her fiction. With Tove, it feels as if numerous blanks have been filled in regarding the author—assuming we've ever given much thought to the Moomins' creator; for so many of us, this engrossing, intelligent film tells a story we didn't know we were waiting to hear.

Darren Arnold

Images: kallerna [CC BY-SA 3.0] / BFI

_Collections%20CINEMATEK%20(C)%20Fondation%20Chantal%20Akerman%20(3).jpg)

_Collections%20CINEMATEK%20(C)%20Fondation%20Chantal%20Akerman%20(4).jpg)

_Collections%20CINEMATEK%20(C)%20Fondation%20Chantal%20Akerman%20(5).JPG)

%20(Akerman).JPG)

_Collections%20CINEMATEK%20(C)%20Fondation%20Chantal%20Akerman_1.3.2.tif)

.jpg)

NGF.jpg)

![Moomin World, Naantali. Image: kallerna [CC BY-SA 3.0]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiRam_KKG18835CeKpHT6ZLkGNm5TtAcNaZVjm1uIFhqzD4v37u2OdTEvv-oZFnhQ1cc4GTIQTj32pFtv3e0T0xZKmHmW4OoAMZnjfd5lxUB6WQ13twANTN8G0g0OU7pRRQ2oM2WJTWINM/w320-h248/Muumin%25C3%25A4ytelm%25C3%25A4_Teatteri_Emmassa.jpg)